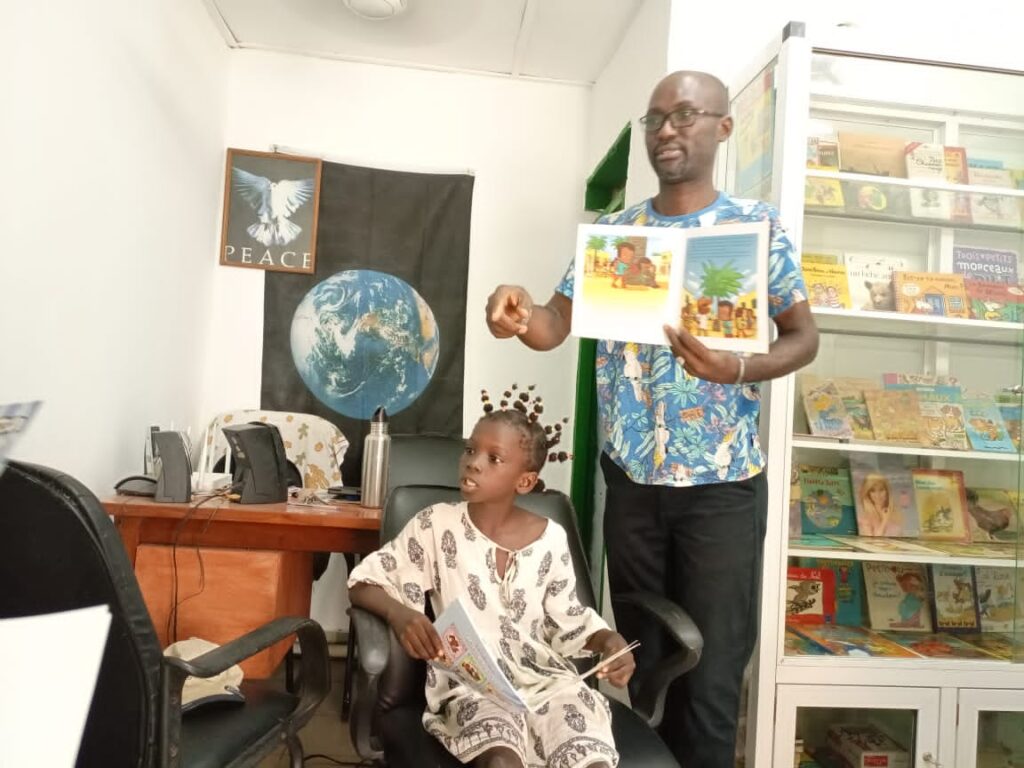

Transforming a Barbershop into a Children's Library

One day recently, James Offuh, 2022 Goldin Global Fellow and Founder of United for Peace Against Conflicts International (UFPACI) from Côte d’Ivoire, saw kids playing with his barber tools. Realizing the hazards here, he instead offered them some books as an alternative which saw the creation of his Peace Library Project.

This seemingly random moment created a positive change for the kids in his community, highlighting how we can play our part in creating social change by leveraging the resources we already have. As a result, James, a peace advocate and educator, initiated the Children Transformative Literacy Peace Library Project and contributed to a visioning summit by launching a parenting toolkit in his community.

In this piece, he speaks more about this initiative’s impact on the children and their families, the challenges faced, and the driving inspiration behind this transformative work.

A Library Provides a Safe Space for Children

Before the creation of the peace library, which is entirely free to use, James states that children loitered on the streets, playing harmfully like throwing stones at each other, interacting with abuses like rudeness and arrogance, showing hateful sentiments, and being apathetic to one another.

“In contrast, now major outcomes are that children around my community have found a safe space for learning virtues, values that support good moral behaviors.” he says. Further, he believes – through such initiatives – children are more likely to be exposed to peace, justice, social cohesion, and accountability values “Most importantly children are developing interest in books, learning to read and always visiting the book station as a place of socialization.”

He highlights the role of the ‘Assets Based Community Development’ approach by valuing it as a critical principle to uncover gifts within our community, focusing on what’s “strong” rather than what’s “wrong”.

“When planning a community-driven social change mechanism and action frameworks, such as transforming my barbershop into a community peace library to address early child illiteracy and juvenile crimes, one should pay more attention to the gifts as opposed to deficits in society.”

— James Offuh

James remarks that many children do not have the necessary parenting guidance or resources, which often leads to children and teens getting involved in criminal activities, hard drug deals, and the consumption of marijuana.

This often meant they were sent into juvenile crimes that became alarming in the Abobo town in Abidjan City. James gives a perspective on how this alternative education space outweighs some traditional ways to solve this social problem.

“I discovered that these children, most of them grew up on the streets, had no good moral education background, applying punitive, coercive measures will not solve the problem holistically, as police keep making arrests, imprisonments, etc.“

— James Offuh

Transformational Peace through Asset Based Community Development

Further, James speaks on how, in his everyday work at the UFPACI, he implements the knowledge gained during his time as a Goldin Global Fellow: “Goldin Institute’s Gather program was an eye-opener to me; before the program, I did not know about the terms ‘ABCD’ approach and Community Driven Social Change action.” Moreover, he recalls how adaptive leadership versus technical leadership helped him understand more conflict sensitivity, analysis, and ‘do no harm’ as a tool for diagnosis over individualistic versus relational context.

Goldin Institute expanded his global connections, too. “The Gather program expanded my networking, and I got a partner from the U.S.A. who visited me here in Cote d’Ivoire and got my details from the Goldin Institute website. He is also a member of the Gather Global Alumni network.” James also gained free online training workshops, participating recently in Project Management and Strategic Planning, which helped him learn how to design, plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate processes and outcomes.

Conclusively, James leaves us with a saying from Fredrick Douglas:

“It’s easier to build strong children than to repair broken adults.”

With his tireless work and activism at UFPACI, James and his team promote social dialogue, a non-violent culture, and peace reinforcement. Read more about their work and find ways to support them by checking their website: https://ufpacidialogue.net/. You will support the library’s longevity and sustainability so it can serve as many children for as long as possible.

Currently, the library needs infrastructural support like stable internet connectivity, electricity, comfortable reading seats and tables, workshop toolkits like drawing materials, and story books in English and French language.

Swingset Activism: The Promise of Social Justice Education Inspired by Childhood

By David C. Metler, 2022 Goldin Global Fellow

“Swingset activism asks us to close our eyes and feel that exhilarating liberation you feel as a child on a swing soaring to new heights, perspective, and possibilities.”

Confucius once said that “we have two lives, and the second one begins when we realize we only have one.” I am convinced that social justice education has two awareness deepening lifecycle journeys. The first begins when you connect your personal experience to a systemic level and the second one begins when you realize social justice begins with childhood.

Integrating the Two Journeys

My first formal social justice education experience involved volunteering as a part of the Pangaea World Service Team in Nicaragua when I was a college student at the University of Michigan. It devastated me to learn about the leading role the US has played historically in keeping Nicaragua in poverty. I experienced what Bobbi Harro calls a “critical incident” which “creates enough cognitive dissonance that a change is initiated within the core of a person about what they believe about themselves”. Paulo Freire calls this “conscientizacao” – a transformative process from object to subject that lit my soul on fire for social justice.

Upon returning from this trip, I joined the social justice education University of Michigan’s Program on Intergroup Relations (IGR). Through social justice dialogues, I began to develop critical consciousness around identity, power, privilege, and oppression across personal, interpersonal, institutional, and systemic levels. An IGR mentor told me that there was a book, Parenting for Social Change by Teresa Graham Brett that would “blow my mind.” It completely did.

In bringing together parenting and social change, Teresa integrated her previous social justice education experience around identity and power (being a past co-director of IGR at UM) into her relationships with children. Teresa approached her relationships with children as a personal arena for practicing social justice which was integral to her pursuit of justice in the world. Her book helped me begin to see how a transformation of childhood could transform the world as I realized that there were profound lessons from the wisdom of children and childhood experiences that were invaluable for social justice education and activism.

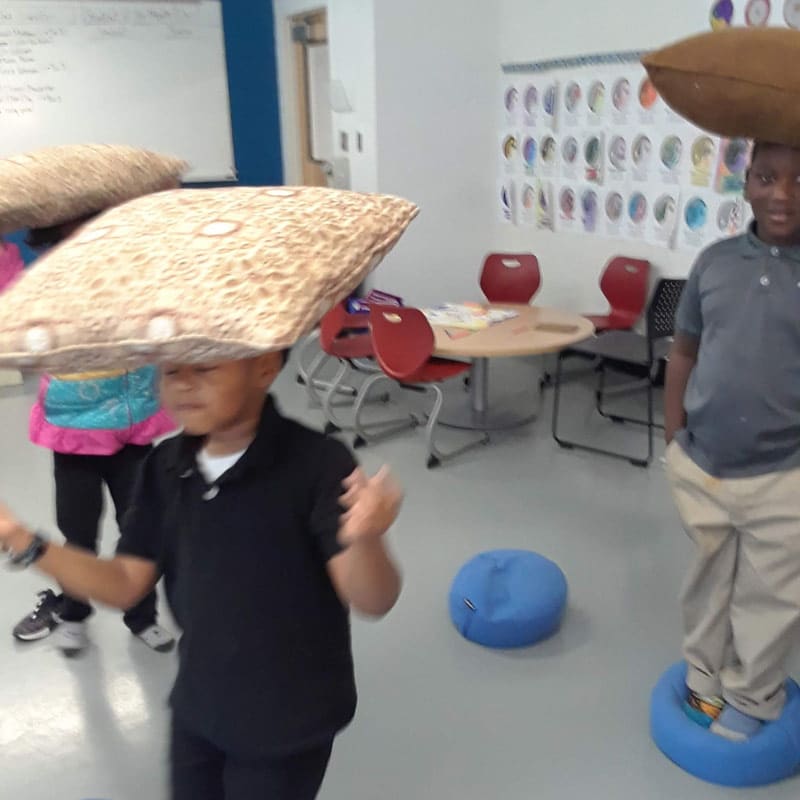

For more than ten years I have worked with leading child and family activists from across the globe and since 2020, I have created the original concept of Swingset Activism which is currently being studied with a grounded theory approach through creative social justice education with the next generation of changemakers from across the globe. Swingset activism asks us to close our eyes and feel that exhilarating liberation you feel as a child on a swing soaring to new heights, perspective, and possibilities. Swingset Activism is a new type of activism inspired by childhood. There are many types of activism like environmental activism, relational activism, consumer activism, or design activism. Each offers a specific approach and focus lens to changemaking. Swingset Activism is activism generated by love that is integrative, relational, and imaginative. Swingset Activism brings together Ecological Systems Theory (Integrative), Relational Activism (Relational), and the Inner Child (Imaginative). It centers the significance of transforming childhood in activism as a strategy to maximize personal, social, and global transformation.

Swingset Activism brings forth a new level of awareness which catalyzed my search for my own authentic voice at the root of my passion for social justice. As I meditated on finding my inner child’s authentic voice for social justice, what came up for me is the earliest experience of being in the womb is lived experience of the profound interconnection and interdependence of human nature, and for the first few years of infancy there is no “other”. This is important to remember in pursuits of solidarity and partnership in social justice. It is our true nature. It is our original sense of inter-being that acknowledges that all of our liberation is bound together. Through the integration of these insights and practices the elasticity of my own mindset expanded of the whole world being one family and that children are, as Carol Stack would say, “all our kin”.

Understanding the wisdom of my inner child also brought back memories of having a clear, innate sense of right and wrong as a child. This recollection reminds me as an adult that the pursuit of social justice is not performative, but intuitive and relational.

Activism as Relationship

Swingset Activism offers the insight that not all activism is done by “activists.” In their seminal academic article, “Relational Activism: Reimagining Women’s Environmental Work as Cultural Change” Sarah O’Shaugnessy and Emily Kennedy introduce the term “relational activism” for how we approach our personal and private lives that directly affect social change. Relational activism captures the behind-the-scenes, private sphere, community-building work of activism and highlights the importance of community, networks, and communication in contributing to long-term social change. Relational activism values public and private sphere actions equally while honoring the moments of social justice that happen within daily routines and in daily relations with others. For activism to be innovative and to generate a sustainable lifestyle, it needs to live within everyday moments of relationship, especially in building equal power relationships across social identity differences.

I believe that for activism to be integrated into a lifestyle it needs to relational and embrace elements of playfulness, joyfulness, loving-kindness, presence, creativity, and our capacity to re-imagine what’s possible. The process can then match the goal of social justice from integration of these valuable ways of being that children embody most regularly into activism. Audre Lorde says, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” which calls upon our imagination and creativity in approaching social justice. I believe it acknowledges the wise contributions of children and childhood experiences in activism. It also serves as a reminder of the solidarity and sacrifice of children and youth literally being on the front lines of social justice movements throughout time, which is not credited since history is typically told by adults.

Intentionally approaching integrity in activism also requires looking critically at what I call the “activist paradox” exploring the ways in activists unconsciously recreate systems of oppression, linked to experiences of oppression in childhood within social justice efforts. Paying attention to these paradoxes will highlight the continual inner work adults need to do to heal their inner child. From reflecting on my childhood, I am able to begin a process of integration that allows me to link the change I wish to see in the world; in myself and my daily routine, ways of being, and relations with others. I have learned to view activism in a relational way that practices social justice in everyday moments, with change happening at the speed of trust, and inner and outer change being interdependent across levels.

Imagining a Transformed World

As an activist, there is a desire to see clearly the roots of injustice and oppression so that efforts to create change actually transform the systems of oppression and not just the symptoms of oppression. It is known that the nature of oppression is non-hierarchical and intersectional but less known is how oppression is foundational in childhood. The wisdom of the science of relationships has revealed how our earliest relationships set a blueprint for relationships over the lifespan.

Since the oppression of children is the earliest, most normalized, and rationalized form of oppression; it provides the foundation for other forms of oppression because the first relationships in childhood root initial experiences with the common elements of oppression. These common elements of oppression are core to adultism, (the supremacy of adults over children), and underlie oppression in any form:

(1) a false notion of superiority across an identity difference becoming seen as an inherent belief that one identity group is superior to another and

(2) this belief being enforced as justification for the superior group to normalize its power and control over the other to maintain its superiority.

Adultism sets an invisible infrastructure for other socially constructed power-over divides across social identity to find deep hold, especially because children face the oppression of adultism with the least control and capacity to resist or language to make sense of the experience. Oppression then becomes internalized and normalized and the oppressed then become the oppressors, but oppression can be uprooted with the unlearning of adultism and the empowering of children, which is called childism, similar to feminism but for children.

Potentially, the most promising aspect of Swingset Activism, which focuses on social justice beginning with childhood, is that oppression is not only foundational in childhood it is notably the one oppression that all adults have common experience with – although there is difference in how adverse childhood was, everyone experiences adultism in some form during childhood. For example, despite increasing awareness of the commonality of Adverse Childhood Experiences, ACES, the overall experience of childhood involves a lack of control and domination over children by parents, teachers, and a larger institutional and societal culture of adultism. Because all adults were once children and still carry their childhoods within them, the convergence of adulthood and childhood can be comprehended in the mind and the profound interconnection of adult and inner child felt in body.

This shared experience presents an opportunity like no other for interest convergence, a concept that posits that there will only be social justice progress when it is perceived to be in the mutual interests of both the privileged and the oppressed. Unlearning adultism may provide the simplest convergence of mutual interest across a social identity power divide because it so plainly illuminates how deeply our liberation is literally bound up with one another and how adults and children are equal partners in the pursuit of social justice. Adults cannot be truly free until children are free, and until adults heal their inner child from the internalized oppression of their own childhood.

Swingset activism asks us to close our eyes and feel that exhilarating liberation you feel as a child on a swing soaring to new heights, perspective, and possibilities. As Teresa Graham Brett wisely reminded us, we can in full swing begin to “imagine a world where mistrust, power-over dynamics, domination, and oppression no longer exist because children have never experienced them.” We can begin to create a new story of childhood that creates lasting social justice and the transformation of what is possible.

If you would like to be a part of the founding of the Swingset Institute, please contact me at davemetler@gmail.com!

Sincerely,

David Charles Metler

2022 Goldin Global Fellow

Founder, Inner Passport

Philippines Update: Adopt a School of Peace Summit

Children Living in Conflict-Torn Region Would Benefit Directly From Proposed "Peace School"

As part of her ongoing work in Mindanao, Global Associate Dr. Susana Salvador-Anayatin hosted the Adopt a School of Peace summit in Cotabato City, Philippines on Mar. 23, 2011. Community leaders are engaging government officials, teachers, members of the military, former child soldiers and grassroots groups to create an elementary School of Peace and peace-studies curriculum for children living amidst the ongoing conflict in Mindanao.

In attendance were sixteen key influence makers and concerned organizers from the communities they serve, including former child soldier and current Goldin Institute Advisor Khanappi K. Ayao who welcomed the participants and set the tone for the day with his introduction:

[quote] It is our hope that this meeting will yield a positive response to pursue the project, Adopt a School of Peace in order to facilitate the long-awaited peace and development in our Province."[/quote]

Also welcoming the attendees was Naguib G. Sinarimbo, the Executive Secretary and a direct representative for the Regional Governor of Mindanao (the Honorable Ansaruddin A. Adiong). He specifically thanked Dr. Anayatin and her work on behalf of the Goldin Institute for initiating the project, reminding the participants that "more than any other region in the Philippines, the (Mindanao) Province is an area most in need for all forms of assistance. Any undertaking that will support the regional government in attaining peace is welcome."

Also welcoming the attendees was Naguib G. Sinarimbo, the Executive Secretary and a direct representative for the Regional Governor of Mindanao (the Honorable Ansaruddin A. Adiong). He specifically thanked Dr. Anayatin and her work on behalf of the Goldin Institute for initiating the project, reminding the participants that "more than any other region in the Philippines, the (Mindanao) Province is an area most in need for all forms of assistance. Any undertaking that will support the regional government in attaining peace is welcome."

The School of Peace project has six specific objectives that would form the cornerstone for the proposed school:

- To develop modules for children in public and private schools in Mindanao that would promote non-discrimination; respect for other's beliefs, opinions and cultural practices, and an appreciation of the plurality of cultures and ideas in Mindanao.

- To teach children conflict resolution by teaching them with ways to work out differences and conflicts using peaceful means.

- To integrate the modules into relevant and appropriate core academic subjects.

- To develop and implement training courses for teachers to prepare them for using the modules in the classrooms.

- To equip teachers and parents with the knowledge and skills that they can use to train fellow teachers and parents in using the peace modules.

- To establish the mechanisms that will ensure the sustainability of the project.

Some background of the Province and the current atmosphere for conflict was summarized and gave reference to how the six objectives should be thought of when considering the overall approach to the Peace School plan:

In the context of Mindanao, Philippines, a tri-people land, differences in culture and ideology abound. There is a beauty in the differences if each would respect each other. But reality paints a different picture. A child may hear a slur about Christians or Muslim or Indigenous Peoples from his or her family. He or she may even be warned against relating to those different from them – warning their children that the others cannot be trusted. The teachers themselves, who also grew up hearing the same, sometimes reinforce those beliefs and fears in school.

But we believe that the school is still the primary venue to learn good values, morals, and positive life skills. These should be venues that would promote respect, acceptance, an an appreciation of the differences of beliefs, culture and opinions. These are venues where cooperation and constructive conflict resolution should be practiced and upheld.

It is in this light that we are proposing to adopt a School of Peace – elementary level, located at a nearby conflict-affected area in the Maguinanao Province in Mindanao, Philippines. Modules to be developed will guide teachers on how to discuss the concepts of peace, human rights and conflict resolution in their classrooms. The main part of the Modules leads teachers to explore and reflect on the concepts and issues related to peace building.

Six topics to be introduced as essential to building a Culture of Peace:

- Achieving Personal Peace

- Dismantling Structural Violence

- Respecting Human Rights

- Looking to the past to find Peace Models

- Selecting Peaceful Ways in Dealing with Conflict

- Exploring the Relationship between Nature and Peace